🔹 1. Do they have a common backbone?

Yes.

Most of these drugs are GLP-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1 RAs) — meaning they mimic glucagon-like peptide-1 (GLP-1), a hormone your body naturally makes in the gut after meals to trigger insulin release, slow gastric emptying, and reduce appetite.

The “backbone” is essentially the amino acid sequence of human GLP-1 (a short peptide, 30–31 amino acids). Drug companies take this natural peptide and modify it so that:

- It resists breakdown by DPP-4, an enzyme that normally degrades GLP-1 within 2 minutes.

- It lasts longer in the bloodstream (hours to days instead of minutes).

- It binds strongly to the GLP-1 receptor.

So the natural backbone = human GLP-1 sequence. The drugs are engineered derivatives of this sequence.

🔹 2. Where does that backbone come from? Is it natural?

The starting point is natural GLP-1, which is encoded in the human proglucagon gene. But the drugs themselves are synthetic — they aren’t extracted from animals or plants. They’re made in labs using peptide synthesis (solid-phase chemistry) or via recombinant protein expression in engineered bacteria or yeast.

So:

- Inspiration = natural human peptide.

- Manufacturing = fully synthetic or bioengineered.

🔹 3. How are new peptides found and created?

There are two main routes:

a. Natural analogues

Scientists screen other species for GLP-1-like molecules.

- Example: Exenatide (not listed in this article) came from the saliva of the Gila monster lizard, which contains exendin-4, a GLP-1-like peptide resistant to DPP-4.

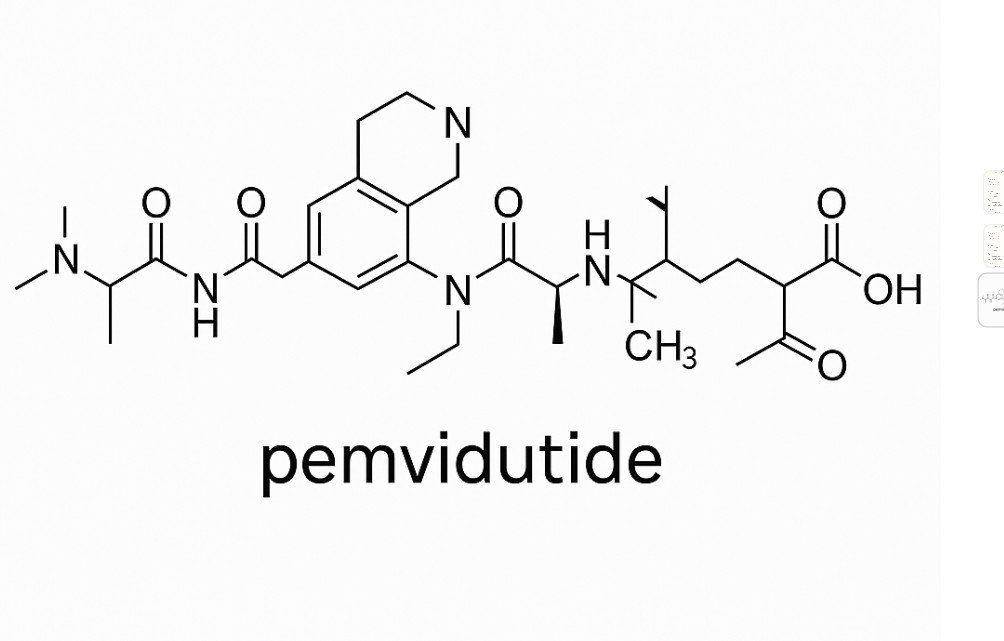

b. Rational design

Chemists and biologists modify the amino acid sequence of GLP-1 or combine it with other peptide hormones.

- Swap amino acids to resist degradation.

- Add fatty acid side chains (so the peptide binds albumin and circulates longer).

- Fuse to Fc fragments (antibody piece) or other proteins to slow clearance.

- Combine two different hormone domains (dual/triple agonists like tirzepatide and retatrutide).

High-throughput screening, computational protein design, and structure–activity studies are used to test variants until one has the right balance of stability, potency, and duration.

🔹 4. The actual differences between these compounds

| Drug | Type | Modifications / Features | Half-life | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

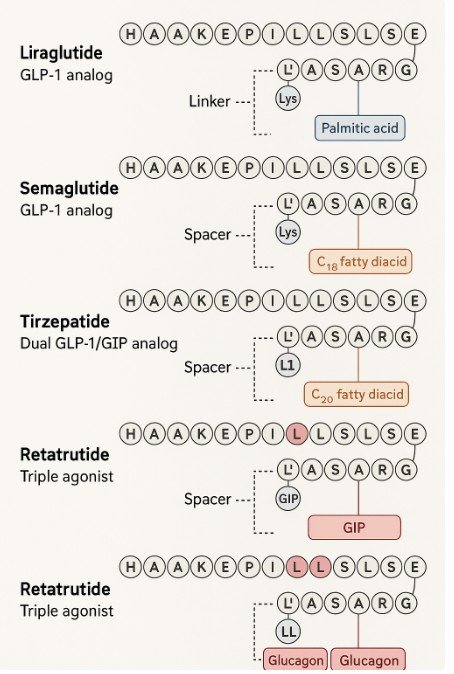

| Liraglutide | GLP-1 analog | Palmitic acid side chain + linker → binds albumin, resists DPP-4 | ~13 hrs | Daily injection |

| Dulaglutide | GLP-1 analog | Fused to Fc fragment of IgG4 antibody → huge size prevents breakdown | ~5 days | Weekly injection |

| Semaglutide | GLP-1 analog | C18 fatty diacid side chain + spacer → strong albumin binding | ~7 days | Weekly injection (oral & injectable forms exist) |

| Lixisenatide | GLP-1 analog | Modified exendin-4 derivative with extra lysines | ~3 hrs | Once-daily injection |

| Tirzepatide | Dual GLP-1 + GIP agonist | Hybrid peptide that activates both GLP-1 and GIP receptors | ~5 days | Weekly injection; superior weight loss |

| Retatrutide | Triple agonist (GLP-1, GIP, glucagon) | Engineered peptide with domains from multiple incretins | ~5–7 days | In clinical trials; shows very strong weight loss |

🔹 5. Key takeaway differences

- Backbone: All are inspired by GLP-1 (except exendin-based drugs, which are reptile peptides).

- Stability: Modified amino acids, fatty acid chains, Fc fusions make them last longer.

- Receptor targets:

- First-gen (liraglutide, semaglutide, dulaglutide, lixisenatide) = GLP-1 only.

- Next-gen (tirzepatide, retatrutide) = multi-agonists hitting GLP-1 + other incretins.

- Duration: From hours (lixisenatide) → to weekly (semaglutide, tirzepatide, retatrutide).

- Potency: Multi-agonists generally cause more weight loss and metabolic improvements.

✅ In short: They all trace back to the natural GLP-1 peptide your body makes. Pharmaceutical chemists modify the sequence and structure to make them stable, long-lasting, and sometimes multi-targeted. They’re made synthetically, not “harvested,” and new ones are discovered through a mix of nature-inspired analogues and rational protein engineering.